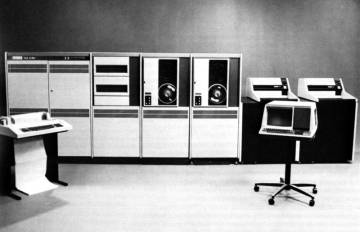

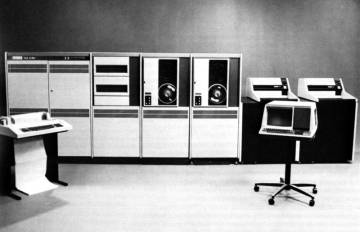

(This picture of a VAX 11/780 is from

Wikipedia

at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VAX

.)

No. 2007-1056

(Serial No. 09/947,801)

IN RE JED MARGOLIN

Appeal from the United States Patent and

Trademark Office

Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences.

APPELLANT’S REPLY BRIEF

Dated: March 1, 2007

Jed Margolin

Applicant, Appellant, pro se

1981 Empire Rd.

Reno, NV 89521-7430

(775) 847-7845

xxx@yyy.zzz

page

TABLE OF CONTENTS ………………………………………………............……. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES …...………………………………………….............…. iii

ARGUMENT ……………………………………………………….…..…….............. 1

The Solicitor makes the new

argument that Margolin’s Home

Network Server is a Personal

Computer and presents it as a fact ..……….....….. 1

Is Margolin’s Home Network

Server a personal computer because

it includes a CPU, memory,

video display, and a keyboard? ………….....……… 4

Is it possible for a specification

to be so broad as to make it

inadmissible as prior art?

…………………………………………………….......... 7

The Solicitor criticizes

Margolin’s patent application

for not being long enough

………………………………………………..........……. 12

The Solicitor fails to respond

to several of

Margolin’s material points

………………………………………………...........….. 14

The Solicitor finally addresses one of Margolin’s arguments .…………….......… 15

The Solicitor misrepresents

BPAI by implying terms must be located

in a particular location

in the Application ………………………………...........…. 18

The Solicitor misrepresents Margolin …………………………………........……. 19

The Solicitor’s opinion on infringement is wrong …………………………........... 20

The Solicitor erred in asserting

that the examiner set forth

a prima facie case of anticipation

……………………………………….......….… 21

The Solicitor has improperly

narrowed the issues …………………………........ 25

i

After Margolin’s Brief was

filed, the Examiner’s

Interview Summary for 8/5/2005

was altered ……………………………........… 26

This Court is a Court of Equity as well as a Court of Law ………………...….....27

CONCLUSION ……………………………………….……….….…………........... 31

ADDENDUM

I. U.S. Constitution Article I, Section 8 ……………………………...........…. 32

II. 35 U.S.C. 102 ……………………………………………………........…… 34

III. 35 U.S.C. 261 …….…………………………………………………......… 35

IV. U.S. Constitution Amendment V …………………………………..…..... 36

V. U.S. Constitution Article III, Section 2 ……..….……………………......... 36

VI. The Judiciary Act of 1789 ………………..…………………………........ 37

VII. Altered Document ………………………………………………....…… 40

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE …....……………………………………...…....... 41

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

.…………………..………………...…........ 42

ii

U.S. Constitution

U.S. Constitution Article I, Section 8 ………........……………………… 27

U.S. Constitution Article III, Section 2 …………………………........…... 30

U.S. Constitution

Amendment V ………………………………….......... 28

Statutes

35 U.S.C. 102 ……………………………………………………........… 11, 27

35 U.S.C. 261

…………………………………………………........…… 27

Legislation

The Judiciary

Act of 1789 ……………………………………….......…. 30

Other Authorities

Federal Register 71FR48

(Docket No.: 2005-P-066) …………….... 10

iii

The Solicitor makes the new argument

that Margolin’s Home

Network Server is a Personal Computer

and presents it as a fact

The Examiner rejected Margolin’s claims by asserting that Ellis’ Network Server 2 (NS2) was the same as Margolin’s Home Network Server. 2 Even in the Examiner Summary for the Telephone Interview of August 25, 2005 the Examiner was still saying it was Ellis’ Network Server 2 that was Margolin’s Home Network Server. (A136) Margolin has shown in his Appeal Brief to BPAI (A145) and in his Appeal Brief to this Court (starting at Br. at 16) that Ellis’ Network Server 2 is not a Home Network Server. Ellis’ Network Server 2 is the ISP’s server and does not perform Ellis’ distributed computing. Ellis uses only his personal computers to perform distributed computing.

It was not until Margolin filed his Appeal Brief before BPAI that the Examiner (in his Examiner’s Answer) asserted that Ellis’ Personal Computer (PC) was a Home Network Server because it sometimes acted as a server. (A158, A159, and A160) BPAI agreed with the Examiner. They did not assert that Margolin’s Home Network Server was a personal computer. (A3-A6)

---------------------------------

[1]

References to the Appendix are made by “A_ “, to Margolin’s brief by “Br.

at _”, and to the Solicitor’s Brief by “SBr. at_”.

[2] In the First Office Action the Examiner cited sections of Ellis. (A26 and A27). In the Second (and Final) Office Action the Examiner specifically pointed to Ellis’ Figure 2 Item 2 (A99, A100, A101, and A103) which is Ellis’ NS2 (A35).

1

Margolin has shown that Ellis’ PC is not a Home Network Server in his Response to the Examiner’s Answer (A169, A170) and in his Appeal Brief to this Court (Br. at 21) Ellis’s PC is not a server. Ellis himself distinguished his PC from a server in order to persuade his Examiner to allow the patent.

Left with nowhere else to go the Solicitor now makes the argument that Margolin’s Home Network Server is a personal computer. (SBr. at 3) What is the standard of review for a brand new argument that does not appear in the record? The Solicitor has asked for a standard of review of “substantial evidence.” “Substantial evidence is something less than the weight of the evidence but more than a mere scintilla of evidence.” (SBr. at 9) Therefore, the Solicitor is asking the Court to give his argument more weight than Margolin’s. He wants to stack the deck.

That leaves a standard of review of de novo, yet a standard of review is a standard of review of the record. And this new argument has no record other than in the Solicitor’s Brief. As the Solicitor skillfully (and prejudicially) inserted into his STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE (SBr. at 1), Margolin is acting pro se. As a pro se Margolin is at a loss to suggest to the Court the proper standard of review for the Solicitor’s new argument. Perhaps it would be best to simply strike it from the Solicitor’s Brief.

2

The Solicitor argues (SBr. at 3)

The specification discloses that server 101 is connected to the Internet through modem 103. A14, line 13. The specification also states that:And then (SBr. at 12)Home Network Server 101 is of conventional design and includes a CPU, memory, mass storage (typically a hard disk drive for operations and a CD-ROM or DVD-ROM Drive for software installation), video display capabilities, and a keyboard.A14, lines 3-6. Thus, the server can be a PC.

It was reasonable for the Board to interpret Margolin’s home network server as met by Ellis’ PC, A4-6, because PCs generally include a CPU, memory, video display and keyboard, and thus fit Margolin’s exemplary server. Significantly, Ellis defines a PC “as any computer digital or analog or neural, particularly including microprocessor-based personal computers having one or more microprocessors.” A44, col. 8, lines 61-64.

There are two parts to this:

1. Is Margolin’s Home Network Server a personal computer because, like personal computers, it includes a CPU, memory, video display, and a keyboard?

2. Ellis defines a personal

computer as just about everything that has ever been invented or ever will

be invented.

Let’s start with the first part.

3

The Solicitor presents his argument in his STATEMENT OF THE FACTS. His argument is not a “fact.” It is an unwarranted conclusion that shows his lack of knowledge of computers in general and both personal computers and servers in particular.

The Solicitor makes much of Margolin’s statement that his Home Network Server is of conventional design. (SBr. at 3)

The specification also states that:Home Network Server 101 is of conventional design and includes a CPU, memory, mass storage (typically a hard disk drive for operations and a CD-ROM or DVD-ROM Drive for software installation), video display capabilities, and a keyboard.

Yes, Margolin’s Home Network Server

101 is of conventional design. It is of conventional design for a

server,

which is why Margolin called it a Home Network Server and not a

Home Network PC or a Home Network Something-Else.

Not all computers that use CPUs, memory, mass storage, video display capabilities, and a keyboard are personal computers. Computers with these elements existed even before IBM introduced the Personal Computer in August 1981.

4

For example, there was the VAX 11/780 brought out by Digital Equipment Corporation in 1977. It had a CPU (Central Processing Unit), memory, mass storage, video display capabilities, and a keyboard. But it was not a personal computer.

(This picture of a VAX 11/780 is from

Wikipedia

at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VAX

.)

Note that a CPU (Central Processing Unit)

does not automatically mean “microprocessor”. Before there were microprocessors,

CPUs came on printed circuit boards (sometimes several large printed circuit

boards) containing small-scale and medium-scale integrated circuitry. Before

that, they were made of discrete transistors. Before that, they used vacuum

tubes, such as the ENIAC which is described in U.S. Patent 3,120,606 Electronic

Numerical Integrator and Computer issued February 4, 1964 to Eckert

and Mauchly. The ENIAC was not a personal computer.

(This picture of the ENIAC is from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ENIAC

.)

5

Neither was the Harvard Mark I (1944) which used mechanical gears and electromechanical relays, but if the Harvard Mark I had been connected to a video display the Solicitor would have proclaimed it a personal computer.

(This picture of the Harvard Mark I is from the IBM archives.)

There is a good reason why today’s servers use mostly the same hardware as personal computers. The hardware used in personal computers is inexpensive and readily available. What makes a server different from a personal computer is the specialized software that makes it a server. (A96)

Now the Solicitor wants to erase that difference by making all servers personal computers.

Ellis distinguished his personal computers from servers in order to get his patent. (Br. at 21) If the Solicitor is successful in defining servers as personal computers the Ellis patent would be invalidated. That would not be fair to Inventor Ellis. There may also be other patents involving servers that would be affected.

6

The second part of the Solicitor’s argument is that Ellis defines a personal computer as just about everything that has ever been invented or ever will be invented. Ellis certainly does define a PC very broadly as (A44, col. 8, line 61 – A45, col. 9, line 16):

any computer, digital or analog or neural, particularly including microprocessor-based personal computers having one or more microprocessors (each including one or more parallel processors) in their general current form (hardware and/or software and/or firmware and/or any other component) and their present and future equivalents or successors, such as workstations, network computers, handheld personal digital assistants, personal communicators such as telephones and pagers, wearable computers, digital signal processors, neural-based computers (including PC's), entertainment devices such as televisions, video tape recorders, videocams, compact or digital video disk (CD or DVD) player/recorders, radios and cameras, other household electronic devices, business electronic devices such as printers, copiers, fax machines, automobile or other transportation equipment devices, and other current or successor devices incorporating one or more microprocessors (or functional or structural equivalents), especially those used directly by individuals, utilizing one or more microprocessors, made of inorganic compounds such as silicon and/or other inorganic or organic compounds; current and future forms of mainframe computers, minicomputers, microcomputers, and even supercomputers are also be included.

Yet, during prosecution, Ellis narrowed

the definition of personal computer considerably. At the very least it

specifically excludes servers. From A96:

The Examiner appears to have rejected claims 27-41 because of a belief that UNIX and NT servers can be run on personal computers and can be made to function temporarily as a master personal computer or as a slave

personal computer, as similarly recited in claims 27-41. However, a UNIX or an NT server functions as a server, not as a master personal computer or as a slave personal computer, which require applications not found in UNIX or NT operating systems.

Ellis narrowed his definition of personal

computer during prosecution in order to persuade his Examiner to allow

the patent. But where does that leave the broad definition in the specification?

Is it possible for a specification to be so broad as to make it inadmissible

as prior art?

For example, Ellis defines a personal computer as including neural computers and computers made using organic compounds. That would make it an organic neural computer. The Human brain is frequently considered an organic neural computer.

Consider the case where people form a team to work together on a task. Each person performs a part of that task (distributed computing). They must communicate with each other (networking). They are paid for performing that task (Ellis’ standard cost basis – A48 Col. 15 line 62). The team must determine the identity and reliability of the customer whose task they are performing. Is it a lawful task? Will they get paid? If they have more than one customer they must make sure not to breach the confidentiality of each customer. In other words, the team members must use a mental firewall (also known as good business judgment). Therefore, anyone forming such as team is infringing on the Ellis patent. That includes the Patent Office whose many departments perform different tasks in order to process each Patent Application. (A112)

8

More importantly, such human activities have been going on for as long as there have been homo sapiens. How long that has been is open to debate but it predates Ellis by at least several thousand years. If Ellis’ specification is taken literally and given as much weight as the Solicitor gives it, the Ellis patent is invalid. However, as Margolin has argued (A63) under 35 U.S.C 282, issued patents are presumed to be valid. Since Ellis is an issued patent it must be presumed to be valid. In order to respect this presumption we must overlook Ellis’ definition of a personal computer as including organic neural computers.

As far as defining a personal computer as including a server is concerned, Ellis gave that up during prosecution. He did not give up organic neural computers, yet that part seems to have dropped off the Solicitor’s radar. If the Solicitor wishes to contest the validity of the Ellis patent, this is not the right place for it.

Consider the following hypothetical patent application titled “Multi-Function Flashlight.” The specification defines a flashlight as follows:

A Flashlight is defined in the broadest possible terms as a device (or mechanism, agent, apparatus, appliance, construction, contrivance, contraption, or process) that produces light (or electromagnetic energy or any energy at any wavelength whether currently discovered or may be discovered in the future) through the process of incandescence (or fluorescence, phosphorescence, combustion, chemical reaction, the stimulated emission of radiation, nuclear fission, nuclear fusion, zero-point conversion, gravity-wave phase shifting without or with Heisenberg compensation, or by any process now known or may be known in the future in this or any other dimension of the Multiverse).

The specification lists the functions performed by the multi-function flashlight:

In addition to functioning as a flashlight the current invention also functions as a personal communicator (such as a cell phone or pager), PDA, personal transportation device, personal computer, personal grooming device, or any other useful function. The multi-function flashlight may also contain a solar cell, a rechargeable battery, an electric motor, and one or more wheels (preferably round but other shapes may be used) .

The specification continues:

The preferred embodiment of the Multi-Function Flashlight comprises a cylindrical housing containing every technology ever invented or ever will be invented in the future, although shapes other than cylinders may also be used.A second preferred embodiment of the Multi-Function Flashlight comprises a cylindrical housing, solar cells arranged longitudinally around the cylinder, a lamp at one end of the cylinder, and a set of small rotating blades located at the other end of the cylinder.

A third preferred embodiment includes a number of keys arranged longitudinally around the cylinder and combines a video display with the lamp.

A fourth preferred embodiment includes a speaker located near one end of the cylinder and a microphone located at the other end, and an antenna that extends distally from the cylinder.

The application contains 963 claims

of varying size and scope.

The application is published eighteen months after filing and is examined thirty months after that.

After a short prosecution because the Examiner has used his newly-given discretion to limit the number of RCEs to one (as per 71FR48) the Applicant has narrowed his invention to 195 claims, with claim 1 as follows:

10

1. A personal grooming device comprising:

(a) a motor;

(b) a set of rotating blades;

(c) a solar cell;

(d) a rechargeable battery;

(e) a lamp;

(f) a switch;whereby said solar cell recharges said rechargeable battery, said rechargeable battery provides power to said lamp, said rechargeable battery also provides power to said motor to turn said set of rotating blades, and said switch interrupts the power to said set of rotating blades and said lamp.

In other words, it is a solar powered

shaver with a light.

Whether or not any claims are allowed, the specification is available to future Examiners to issue a 35 U.S.C. 102 rejection to almost every future application for an invention that contains a light. This includes electric cars and bicycles.

There will be markedly more cases going to BPAI and markedly more cases going to this Court.

It would be useful for this Court to develop a philosophy of dealing with specifications that are overly broad (starting with the present case) before the onslaught begins.

Ellis hit his target and got his patent but his shotgun approach to his specification has left a considerable amount of collateral damage.

11

In Statement of the Facts (SBr. at 2) the Solicitor finds fault with Margolin’s Patent Application because he considers it too short.

For example, his section entitled “Detailed Description” (i.e., his written description) is only about two pages. A14-15. His terse description discloses a server using the Internet in combination with a modem and other devices. Id.: A19 (Figure 1).

The patents for some of the greatest

inventions have been short. U.S. Patent 223,898 Electric Lamp issued

January 27, 1880 to Thomas A. Edison was for the first practical incandescent

light. The entire patent (including drawings) is three pages long. U.S.

Patent 836,531 Means For Receiving Intelligence Communicated By Electric

Waves issued October 1906 to Greenleaf Whittier Pickard included a

silicon point-contact diode, the first semiconductor diode. It is four

pages. U.S. Patent 879,532 Space Telegraphy issued February 18,

1908 to Lee de Forest was for the triode vacuum tube, which was the first

device that could amplify the power of an analog signal. It was the basis

for the entire field of electronics for most of the Twentieth Century.

It is also four pages. U.S. Patent 1,342,885 Method of Receiving

High-Frequency Oscillations issued June 8, 1920 to Edwin H. Armstrong

was for the superheterodyne. Almost all radios and televisions today

still use Armstrong’s superheterodyne method. The patent is five pages

long.

12

While Margolin’s current invention might not be as important to Society as the ones cited, they show that the length of a disclosure is not an indication of its value.

The Solicitor refers to Margolin’s terse description. The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (www.m-w.com) defines terse as:

1 : smoothly elegant : POLISHED

2 : devoid of superfluity <a terse summary>; also : SHORT, BRUSQUE <dismissed me with a terse "no">

synonym see CONCISE

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary

(www.etymonline.com), “The pejorative meaning "brusque" is a fairly recent

development.” Since Margolin’s Description is hardly brusque, the Solicitor

appears to be against concise.

13

The Solicitor’s own Brief is short, only approximately 4,500 words. If he had used more words he might have addressed some material points raised in Margolin’s Brief, such as the Examiners denying that the word Home has any common meaning.

The Solicitor failed to address the issue that BPAI adopted a method of claim interpretation that does not represent the position presented to this Court by the Solicitor in his Amicus Curiae Brief in Appeal Nos. 03-1269,-1286 PHILIPS v. AWH CORP. (Br. at 29).

The Solicitor failed to address the Examiner Summary of the Telephone Interview for August 5, 2005. (Br. at 31-36). 3 The Solicitor stated (SBr. at 23):

Thus, not only did the USPTO perform its important task of reaching the correct result in this case, supra, it also showed good faith, professionalism and multiple courtesies to Margolin during the prosecution of his patent application.

This suggests that the Solicitor is

either unfamiliar with the record or condones misconduct and fraud.

---------------------------------

[3]

After Margolin filed his Appeal Brief the Examiner Summary was altered

in the Patent Office Image File Wrapper. Margolin will discuss this

later.

14

The Solicitor did discuss Margolin’s observation that, while the Examiners insisted the Subscriber is a device and not a person, BPAI seemed to understand that the Subscriber is, indeed, a person. (Margolin then questioned how BPAI could find the Examiner’s rejection reasonable.) 4 The Solicitor’s response is:

In making that argument, Margolin seems to be referring to the claim language “whereby the subscriber receives something of value.” A16, line 6 (emphasis added). In that sense, the distinction between a person and a device is stretching semantics too far. If a subscriber’s home network server receives value, the subscriber receives value.(emphasis added)

The Solicitor wants us to believe that making a distinction between a device (home network server) and the person who owns the device (the homeowner) is “stretching semantics too far.”

Let’s call the home network server the “device” and the person who owns the home network server the “person.” In order not to stretch semantics too far, let’s posit that the “subscriber” may be either one. We need to agree that the subscriber cannot be both a device and a person at the same time. Otherwise, we have to argue over what makes a “person” a person, what makes a “device” a

---------------------------------

[4] Margolin’s

argument is at Br. at 27-28. The Solicitor’s comments are at SBr. at 19-20.

15

device, and what makes them different. (Then the Dictionary Police will show up and take everyone into custody.)

In analyzing the sentence “If a subscriber’s home network server receives value, the subscriber receives value” the home network server is the device. The subscriber may be either the person or the device.

The sentence contains one instance of “home network server” and two instances of “subscriber.” Since “subscriber has two possible meanings, the sentence has four possibilities:

1. “If a person’s device receives value, the person receives value.”2. “If the person’s device receives value, the device receives value.”

3. “If the device’s device receives value, the person receives value.”

4. “If the device’s device receives value, the device receives value.”

Statement 2 is redundant.

Statements 3 and 4 are meaningless. The device cannot own itself (unlike

the metaphysical way a person can own himself or herself).

That leaves only Statement 1 as having a valid meaning. The Subscriber is a person and the distinction between a person and a device is important.

Here’s the thing about the Solicitor’s statement. It is not about the Subscriber. The Solicitor’s statement is actually about “value.” He uses it twice and it means something different each time.

16

The first time, it is the device (home network server) that receives value. The second time, it is the person (the Subscriber) who receives value.

Margolin uses “value” in terms that have meaning to a person (a human being) as in, “something of value such as reduced cost of Internet service, free Internet service, or a net payment.” (A12-13, paragraph [0016])

What would something of value be to a device such as a home network server? The question cannot be answered until machines become sentient and we can ask them. In any event, the answer is irrelevant to the point the Solicitor is trying to make to counter Margolin’s argument. Margolin’s argument was: While the Examiners insisted the Subscriber is a device and not a person, BPAI seemed to understand that the Subscriber is, indeed, a person, and because of that, how could BPAI find the Examiner’s rejection reasonable? The Solicitor’s argument failed to provide an answer.

Semantics is “The study or science of meaning in language” (American Heritage Dictionary). This case is all about finding meaning in language. Perhaps the Solicitor should choose his words more carefully lest he give a bad name to the honorable field of semantics and insult those who practice it in good faith.

17

The Solicitor stated (bottom of SBr. at 7 to top of SBr. at 8):

In fact, the Board noted that although Margolin chose to define certain terms at the beginning of his specification, he did not include “server" in his definition-section.What BPAI said was (A4):

We find that the specification at paragraph 2 sets forth certain definitions, but not for the terms in dispute. Upon review of the entire disclosure, we conclude that the “Home Network Server” described embodiment does not convey a limiting definition for the term “server,” nor that the invention is to be limited to the disclosed embodiment.U.S.C 2173.05(a) does not require that when the Applicant defines a term the definition be located in any particular section of the Application nor that it use formulaic language such as, “This term is defined as…” . (A178) Margolin assumed BPAI knew this and was merely trying to sound “judicial.”

Indeed, Ellis did not even have a “Definition-Section.” He defined “personal computer” in his section Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments. (A44, col. 8, line 59 – A45, col. 9, line 16).

Neither the Solicitor nor BPAI had any problem with this. There should not be a different standard for Margolin.

18

The Solicitor stated (SBr. at 13):

Margolin argues that Ellis’ PC is not used

in the “home,” citing as support the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution.

Br. at 12.

Margolin has never argued that Ellis’ PC is not used in the “home.” The page cited by the Solicitor addresses the issue of the Examiners denying Margolin the common meaning of the term “home.” Margolin’s citation of the Fourth Amendment was used in his suggested definition of the common use of the term “home.” (Br. at 12)

19

In discussing BPAI’s decision, the Solicitor

gives his opinion (SBr. at 15):

Put differently, it is clear that if Margolin’s claim issued in a patent, Ellis’ PC-serving-the-ISP features would unquestionably infringe the broad term “home network server” and thus Ellis anticipates. See, e.g., Polaroid Corp. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 789 F.2d 1556, 1573 (Fed. Cir. 1986) (“that which infringes if later anticipates [or meets the claim] if earlier”) (quoting Peters v. Active Mfg., 129 U.S. 530, 537 (1889)).

(Emphasis added)

No, it is not clear. And it is certainly

not unquestionable. Margolin is going to question it right now.

In the Solicitor’s hypothetical infringement case, during the Markman hearing Ellis would point out:

· Ellis does his distributed computing in PCs.· Margolin does his distributed computing in home network servers.

· During the prosecution of his patent Ellis distinguished his PC from a server.

· Margolin distinguished his home network server from a PC in his patent application and during prosecution of his patent. At the very least, he is estopped from asserting that Ellis’ PC is a home network server.

Ellis moves for Summary Judgment which

is swiftly granted.

The End.

20

The Solicitor stated (SBr. at 22):

Margolin also argues that the Board failed to add to the examiner’s case. Br. at 24-27. However, the examiner set forth a prima facie case of anticipation based on Ellis and it was up to Margolin to show error in that examiner’s decision. See Baxter Travenol Labs., 952 F.2d at 391 (arguments made must be specific in order for them to be addressed).

When the Examiner rejected Margolin’s

claims in the First Office Action under 35 U.S.C. 102 (A26) he cited broad

sections of Ellis saying they showed Margolin’s claimed invention. Here

is the Examiner’s rejection of claim 1 (A26):

Claims 1-5 are rejected under 35 U.S.C. 102(e) as being anticipated by Ellis (US 6,167,428).As per claims 1 and 3, Ellis discloses a distributed computing system comprising:

(a) a home network server in a subscriber’s home; (Col 7 lines 66-67, Col 8 lines 1-14 and 23-28)(b) one or more home network client devices; (Col 13 lines 8-29, Figure 9)

(c) an Internet connection; (Col 8 lines 7-10, Col 13 lines 4-7, Figure 1

item 3)whereby the subscriber receives something of value in return for access to the resources of said home network server that would otherwise be unused. (Col 7 lines 38-48, Col 10 lines 1-6)

The Examiner rejected Margolin’s “home network server in a subscriber’s home” solely by citing Ellis Col. 7 lines 66-67, Col. 8 lines 1-14 and 23-28.

Col. 7 lines 66-67 and Col. 8 lines 1-14 are a continuous passage (A44) and say :

For this new network and its structural relationships, a network provider is defined in the broadest possible way as any entity (corporation or other business, government, not-for-profit, cooperative, consortium, committee, association, community, or other organization or individual) that provides personal computer users (very broadly defined below) with initial and continuing connection hardware and/or software and/or firmware and/or other components and/or services to any network, such as the Internet and Internet II or WWW or their present or future equivalents, coexistors or successors, like the MetaInternet, including any of the current types of Internet access providers (ISP's) including telecommunication companies, television cable or broadcast companies, electrical power companies, satellite communications companies, or their present or future equivalents, coexistors or successors.

Col 8 lines 23-28 (also A44) say:

The computers used by the providers include any computers, including mainframes, minicomputers, servers, and personal computers, and associated their associated hardware and/or software and/or firmware and/or other components, and their present or future equivalents or successors.

The Examiner did not distinctly point

out what elements in Ellis formed the reason for his rejection, leaving

Margolin to try to guess what was in the Examiner’s mind.

22

Because the passage from Ellis uses the term “network provider” early on, Margolin guessed the Examiner was referring to Ellis’ Network Server (NS2) as shown in many of Ellis’ figures such as Figure 2, because it belongs to the ISP.

Margolin gave a very detailed response. (A59)

The Examiner confirmed Margolin’s guess

in the Second Office Action (which he made Final) by saying (A99):

As per arguments per claims 1 and 3, applicant

argues:

1. Ellis does not show a Home Network Server. Ellis’s server 2 is part of the

Internet Service Provider’s equipment and is not in the Subscriber’s home.As per section [0014] in the application, applicant states: A Home Network Server is used in a home to network various clients such as PCs, sensors, actuators,and other devices. It also provides the Internet connection to the various client devices in the Home Network. Ellis does show a Home network server (Figure 2 item 2) and it does provide a Internet connection to various client devices (Figure 2 item 3) As far as the subscriber’s home, the Home network server receives the service from the PC. (Col 7 lines 46-4 7) When a device receives a service, is interpreted by the examiner to mean “subscribing” to a service.

Other than confirming that the Examiner

was pointing to Ellis’ Network Server (NS2) the Examiner continued

to make cryptic remarks such as, “When a device receives a service, is

interpreted by the examiner to mean “subscribing” to a service.” This left

Margolin continuing to wonder what the Examiner was thinking.

23

During the three telephone interviews (discussed starting at Br. at 31) the Examiner and his supervisor continued to insist that Ellis’ Network Server (NS2) was Margolin’s Home Network Server.

It was not until Margolin filed his Appeal Brief before BPAI that the Examiner (in his Examiner’s Answer) asserted that Ellis’ Personal Computer (PC) was a Home Network Server because it sometimes acted as a server. (A158, A159, and A160)

Therefore, the Solicitor erred by asserting the Examiner had set forth a prima facie case of anticipation based on Ellis. The Examiner made Margolin do the Examiner’s job for him.

Nonetheless, the Solicitor’s statement that “it was up to Margolin to show error in that examiner’s decision” is correct and Margolin did just that. However, the Examiner simply kept moving the target.

24

In his STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE (SBr. at 1) the Solicitor says, “ Thus, the sole question is whether the Board’s finding that Ellis anticipates representative clam 1 is supported by substantial evidence.”

Margolin disagrees.

There are also the issues of whether Margolin has the right to be his own lexicographer and, when he chooses not to be his own lexicographer, whether he has the right to have the common meaning of words used in interpreting his claims. (Br. at 1-2)

There is the issue of whether BPAI acted properly by adopting a method of claim interpretation that does not represent the position presented to this Court by the Solicitor in his Amicus Curiae Brief in Appeal Nos. 03-1269,-1286 PHILIPS v. AWH CORP. (Br. at 29), This is a subject that the Solicitor failed to address in his Brief.

In addition, as Margolin noted in his Brief, the Examiner’s Supervisor committed fraud on this Court by filing an Examiner Telephone Interview for an interview at which he was not present. (Br. at 31) There is new evidence that pertains to this matter.

25

The document in the Corrected Appellant’s Appendix is a faithful copy of the original that was mailed to Margolin and originally appeared in the Image File Wrapper. (A188 - A190) There are no markings in the upper right corner of the cover sheet. The altered document contains what appear to be initials. 5 Although the purpose of the alteration is not known, the fact is that the document has been tampered with and the Director of the USPTO refuses to investigate the matter. 6

This confirms Margolin’s long-held suspicion

that the Patent Office has engaged in misconduct in this case from the

beginning. The result is that Margolin has been denied Due Process.

---------------------------------

[5]

Addendum, page 40

[6] Margolin faxed a letter to Director Dudas on January 10, 2007 informing him of the alteration but did not receive a reply.

26

1. A patent is a property right created by the U.S. Constitution.

In Article I, Section 8, one of the powers of Congress is:

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries. 7

To underscore the importance of promoting

the Progress of Science and useful Arts Congress has placed the burden

of proof on the Patent Office to show why an inventor is not entitled

to a patent. 35 U.S.C 102, the section under which Margolin’s claims were

rejected, starts with, “A person shall be entitled to a patent unless –

….” 8

2. Patents are personal property.

Under 35 U.S.C. 261, patents have the attributes

of personal property. So do patent applications. 9

Subject to the provisions of this title, patents shall have the attributes of personal property.---------------------------------Applications for patent, patents, or any interest therein, shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing. The applicant, patentee, or his assigns or legal representatives may in like manner grant and convey an exclusive right under his application for patent, or patents, to the whole or any specified part of the United States.

27

3. No person shall be deprived of property without due process of law.

Under Amendment V of the U.S. Constitution

no person shall be deprived of property without due process of law, nor

shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.10

4. Margolin has been deprived of his property without due process of law.

Margolin has been deprived of his rightful property (the patent) and denied due process of law in the following ways:

· The Examiner and his supervisor refused to follow the patent laws which place the burden of proof on them to show why Margolin is not entitled to the patent. A careful reading of the record shows it to be malfeasance.---------------------------------· Further, as described in Margolin’s Brief, on October 12, 2006 the Examiner’s Supervisor wrote and filed an Examiner’s Interview Summary for the August 5, 2005 telephone interview, which was more than 14 months after the interview. Since this was after BPAI issued its ruling and after Margolin filed his Notice of Appeal this Examiner’s Summary was written solely to influence the Court. The Examiner’s Summary was signed only by SPE Rupal Dharia. Since his is the only signature on the Summary it must

---------------------------------

be assumed that he wrote it. However, Dharia was not present during the telephone interview. This is fraud on the Court. (Br. at 32, last paragraph)· After Margolin’s Brief was filed, the Examiner’s Interview Summary was altered. The document in the Corrected Appellant’s Appendix is a faithful copy of the original that was mailed to Margolin and originally appeared in the Image File Wrapper. (A188 - A190) There are no markings in the upper right corner of the cover sheet. The altered document contains what appear to be initials. 11 Although the purpose of the alteration is not known, the fact is that the document has been tampered with and the Director of the USPTO refuses to investigate the matter. 12

· As is also described in Margolin’s Brief, BPAI misrepresented the position of its own agency as presented in the Solicitor’s Brief as Amicus Curiae in Appeal Nos. 03-1269,-1286 PHILIPS v. AWH CORP. Instead of acting as an impartial administrative review court BPAI acted as the Examiner’s advocate. (Br. at 29)

[12] Margolin faxed a letter to Director Dudas on January 10, 2007 informing him of the alteration but did not receive a reply.

29

5. This Court has the authority to order the Director of the USPTO to issue the patent.

This Court derives its authority under Article III, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution which states:

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under

this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which

shall be made, under their Authority; …………… 13

The Judiciary Act of 1789 established

a federal court system combining law and equity into a single court system,

as opposed to the British system where Common Pleas (private law), King's

Bench (criminal law) and Chancery (equity) operated independently, and

derived their authority from the King's writ. 14

Therefore, as in all Federal Courts, this Court is charged with being a Court of Equity as well as being a Court of Law. As a Court of Equity it has the authority to order the Director of the USPTO to issue a patent or to do whatever is necessary in the interests of equity.

---------------------------------

[13]

Addendum, page 36

[14]

Addendum, page 37-39

30

As a Court of Equity, this Court has the

authority to order the Director of the USPTO to issue a Notice of Allowance

for Margolin’s patent application, and Margolin respectfully requests that

this Court do so.

Respectfully submitted,

_________________________

Jed Margolin

March 1, 2007

31

Addendum

Section 8

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

To borrow money on the credit of the United States;

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization, and uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States;

To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures;

To provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States;

To establish Post Offices and Post Roads;

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;

To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court;

To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offenses against the Law of Nations;

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term than two Years;

To provide and maintain a Navy;

To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

32

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress;

To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings; And

To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

33

35 U.S.C. 102 Conditions for patentability; novelty and loss of right to patent.

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless -

(a) the invention was known or used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country, before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, or

(b) the invention was patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country or in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States, or

(c) he has abandoned the invention, or

(d) the invention was first patented or caused to be patented, or was the subject of an inventor's certificate, by the applicant or his legal representatives or assigns in a foreign country prior to the date of the application for patent in this country on an application for patent or inventor's certificate filed more than twelve months before the filing of the application in the United States, or

(e) the invention was described in - (1) an application for patent, published under section 122(b), by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent or (2) a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent, except that an international application filed under the treaty defined in section 351(a) shall have the effects for the purposes of this subsection of an application filed in the United States only if the international application designated the United States and was published under Article 21(2) of such treaty in the English language; or

(f) he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented, or

(g)(1) during the course of an interference conducted under section 135 or section 291, another inventor involved therein establishes, to the extent permitted in section 104, that before such person's invention thereof the invention was made by such other inventor and not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed, or (2) before such person's invention thereof, the invention was made in this country by another inventor who had not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed it. In determining priority of invention under this subsection, there shall be considered not only the respective dates of conception and reduction to practice of the invention, but also the reasonable diligence of one who was first to conceive and last to reduce to practice, from a time prior to conception by the other.

34

35 U.S.C. 261 Ownership; assignment.

Subject to the provisions of this title, patents shall have the attributes of personal property.

Applications for patent, patents, or any interest therein, shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing. The applicant, patentee, or his assigns or legal representatives may in like manner grant and convey an exclusive right under his application for patent, or patents, to the whole or any specified part of the United States.

A certificate of acknowledgment under the hand and official seal of a person authorized to administer oaths within the United States, or, in a foreign country, of a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States or an officer authorized to administer oaths whose authority is proved by a certificate of a diplomatic or consular officer of the United States, or apostille of an official designated by a foreign country which, by treaty or convention, accords like effect to apostilles of designated officials in the United States, shall be prima facie evidence of the execution of an assignment, grant, or conveyance of a patent or application for patent.

An assignment, grant, or conveyance shall be void as against any subsequent purchaser or mortgagee for a valuable consideration, without notice, unless it is recorded in the Patent and Trademark Office within three months from its date or prior to the date of such subsequent purchase or mortgage.

35

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a

capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment

of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or

in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger;

nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in

jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to

be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public

use, without just compensation.

U.S. Constitution Article III, Section

2

Section 2

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls; to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State; between Citizens of different States; between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

36

The Judiciary Act of 1789

One of the first acts of the new Congress was to establish a federal court system in the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Constitution provided that the judicial branch should be composed of one Supreme Court and such inferior courts as Congress from time to time established. But unlike the legislative provisions, in which the framers clearly spelled out the powers of the Congress, Article III of the Constitution is rather vague on just what the judicial powers should be.

Congress had little precedent to guide it, since in the British system the three court systems -- Common Pleas (private law), King's Bench (criminal law) and Chancery (equity) -- operated independently, and derived their authority from the King's writ. Even during colonial times, when American courts followed English precedent, the frontier society had been too poor in resources and trained personnel to follow British practice. So Congress had, in essence, a clean slate upon which to write. One of the more imaginative steps was combining law and equity into a single court system, thus providing for a more effective and efficient means of delivering justice.

The debate in Congress centered on how much power the Constitution transferred from the states to the federal government. States' rights activists opposed giving the new courts too much authority, while supporters argued that only a strong federal court system could overcome the weaknesses that had been so apparent during the Confederation period.

Looking back, it is hard to envision how the supremacy of the Constitution provided for in Article VI could possibly have been sustained without a strong federal court system, one empowered to review and, if necessary, overturn state court decisions. Otherwise, the country would have been saddled again with thirteen independent jurisdictions and no means to conform them to a single national standard. "I have never been able to see," James Madison wrote in 1832 commenting on the federal courts, how "the Constitution itself could have been the supreme law of the land; or that the uniformity of Federal authority throughout the parts to it could be preserved; or that without the uniformity, anarchy and disunion could be prevented."

The courts of the United States, as much as the legislative and executive branches, have been instruments of democratic government, binding a diverse people together.

For further reading: D.F. Henderson, Courts for a New Nation (1971); Julius Goebel, Antecedents and Beginnings to 1801 (1971); the first volume of the Holmes Devise, History of the Supreme Court of the United States; and Maeva Marcus, ed., Origins of the Federal Judiciary (1992).

--------------------------------------------------------------------

An Act to establish the Judicial Courts of the United States

Sec. 1. Be it enacted, That the supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices, any four of whom shall be a quorum, and shall hold annually at the seat of government two sessions, the one commencing the first Monday of February, and the other the first Monday of August. That the associate justices shall have precedence according to the date of their commissions, or when the commissions of two or more of them bear the same date on the same day, according to their respective ages.

Sec. 2. That the United States shall be, and they hereby are, divided into thirteen districts, to be limited and called as follows, . . .

Sec. 3. That there be a court called a District Court in each of the aforementioned districts, to consist of one judge, who shall reside in the district for which he is appointed, and shall be called a District Judge, and shall hold annually four sessions, . . .

Sec. 4. That the beforementioned districts, except those of Maine and Kentucky, shall be divided into three circuits, and be called the eastern, the middle, and the southern circuit. . . . [T]hat there shall be held annually in each district of said circuits two courts which shall be called Circuit Courts, and shall consist of any two justices of the Supreme Court and the district judge of such districts, any two of whom shall constitute a quorum. Provided, That no district judge shall give a vote in any case of appeal or error from his own decision; but may assign the reasons of such his decision. . . .

Sec. 9. That the district courts shall have, exclusively of the courts of the several States, cognizance of all crimes and offenses that shall be cognizable under the authority of the United States, committed within their respective districts, or upon the high seas; where no other punishment than whipping, not exceeding thirty stripes, a fine not exceeding one hundred dollars, or a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months, is to be inflicted; and shall also have exclusive original cognizance of all civil cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, including all seizures under laws of impost, navigation, or trade of the United States. . . . And shall also have cognizance, concurrent with the courts of the several States, or the circuit courts, as the case may be, of all causes where an alien sues for a tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States. And shall also have cognizance, concurrent as last mentioned, of all suits at common law where the United States sue, and the matter in dispute amounts, exclusive of costs, to the sum or value of one hundred dollars. And shall also have jurisdiction exclusively of the courts of the several States, of all suits against consuls or vice-consuls, except for offenses above the description aforesaid. And the trial of issues in fact, in the district courts, in all cases except civil causes of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, shall be by jury. . . .

Sec 11. That the circuit courts shall have original cognizance, concurrent with the courts of the several States, of all suits of a civil nature at common law or in equity, where the matter in dispute exceeds, exclusive of costs, the sum or value of five hundred dollars, and the United

38

States are plaintiffs or petitioners; or an alien is a party, or the suit is between a citizen of the State where the suit is brought and a citizen of another State. And shall have exclusive cognizance of all crimes and offenses cognizable under the authority of the United States, except where this act otherwise provides, or the laws of the United States shall otherwise direct, and concurrent jurisdiction with the district courts of the crimes and offenses cognizable therein. . . . And the circuit courts shall also have appellate jurisdiction from the district courts under the regulations and restrictions herinafter provided. . . .

Sec. 13. That the Supreme Court shall have exclusive jurisdiction of all controversies of a civil nature, where a state is a party, except between a state and its citizens; and except also between a state and citizens of other states, or aliens, in which latter case it shall have original but not exclusive jurisdiction. And shall have exclusively all such jurisdiction of suits or proceedings against ambassadors or other public ministers, or their domestics, or domestic servants, as a court of law can have or exercise consistently with the law of nations; and original, but not exclusive jurisdiction of all suits brought by ambassadors or other public ministers, or in which a consul or vice-consul shall be a party. And the trial of issues in fact in the Supreme Court in all actions at law against citizens of the United States shall be by jury. The Supreme Court shall also have appellate jurisdiction from the circuit courts and courts of the several states in the cases hereinafter specially provided for and shall have power to issue writs of prohibition to the district courts, when proceeding as courts of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, and writs of mandamus, in cases warranted by the principle and usages of law, to any courts appointed, or persons holding office under the authority of the United States. . . .

Sec. 25. That a final judgment or decree in any suit, in the highest court of law or equity of a State in which a decision in the suit could be had, where is drawn in question the validity of a treaty or statute of, or an authority exercised under, the United States, and the decision is against their validity; or where is drawn in question the validity of a statute of, or an authority exercised under, any State, on the ground of their being repugnant to the constitution, treaties, or laws of the United States, and the decision is in favour of such their validity, or where is drawn in question the construction of any clause of the constitution, or of a treaty, or statute of, or commission held under, the United States, and the decision is against the title, right, privilege, or exemption, specially set up or claimed by either party, under such clause of the said Constitution, treaty, statute, or commission, may be re-examined, and reversed or affirmed in the Supreme Court of the United States upon a writ of error, the citation being signed by the chief justice, or judge or chancellor of the court rendering or passing the judgment or decree complained of, or by a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, in the same manner and under the same regulations, and the writ shall have the same effect as if the judgment or decree complained of had been rendered or passed in a circuit court, and the proceedings upon the reversal shall also be the same, except that the Supreme Court, instead of remanding the cause for a final decision as before provided, may, at their discretion, if the cause shall have been once remanded before, proceed to a final decision of the same, and award execution. But no other error shall be assigned or regarded as a ground of reversal in any such case as aforesaid, than such as appears on the face of the record, and immediately respects the before-mentioned questions of validity or construction of the said constitution, treaties, statutes, commissions, or authorities in dispute.

Source: U.S. Statutes at Large 1 (1789): 73.

39

40

The undersigned hereby certifies that a

true and correct copy of the above foregoing and Attachments has been served

on the Office of the Solicitor for the United States Patent and Trademark

Office by United States Postal Service Express Mail Service to the address

shown below:

Dated: March 1, 2007

_________________

Jed Margolin

Office of the Solicitor

Post Office Box 15667

Arlington, VA 22215

41

This brief complies with the type-volume limitation of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B) and (C) and Federal Circuit Rule 32(a). It is proportionally spaced, has a serif typeface of 14 points or more, and contains 6,031 words as calculated by the Microsoft Word program used to prepare the brief.

Dated:

Reno, NV

March 1, 2007

________________

Jed Margolin

Applicant, Appellant, pro se

1981 Empire Rd.

Reno, NV 89521-7430

(775) 847-7845

xxx@yyy.zzz

42